Kuhn

| Darwinism |

Barfield defines Darwinism in various ways as

- A hypothetical account of the history of the natural world, not in terms of uninterrupted transformation of form into form, but of abrupt substitutions of a new form for an old, rather in the manner of Aladdin's lamps. (EC 8)

- Phylogenesis conceived in terms of causality. (EC 8)

- [The] chronologically arranged evolution of outsides. (SM 101)

They were unparticipated to a degree which has never been surpassed before or since. The habit, begun by the scientific revolution, of regarding the mechanical model constructed by alpha-thinking as the actual and exclusive structure of the universe, had sunk right into them. . . . the last flicker of medieval participation had died away. Matter and force were enough. There was as yet no thought of an unrepresented base; for if the particles kept growing smaller and smaller, there would always be bigger and better glasses to see them through. The collapse of the mechanical model was not yet in sight. . . . Literalness reigned supreme.In Darwin's time, alpha-thinking "had temporarily set up the appearances of the familiar world . . . as things wholly independent of man. It had clothed them with the independence and extrinsicality of the unrepresented itself . . ." (SA 61-63).

For Barfield, Darwinism is simply shoddy thinking.2

- It flies in the face of biological evidence:

- We don't hear very

much about the giraffe's neck these days, but I am getting very tired of

those "stick-like" insects, which fit in so nicely with Darwin. You don't

like freaks, so we'll leave out alternate generation, or the life-history

of the Gordius-fly, described by Agassiz,

or the numerous examples of complex symbiosis and the like that in our

own time Grant Watson has described

s o delicately in his books. No doubt they're at the other end of the scale.

But I should have thought they're was quite enough round about the middle

of the scale to rule out natural selection and adaptive radiation as the

principal factor in their provenance--enough for anyone who is not strongly

biased in its favor to start with. (WA 155, Sanderson is speaking)

- It is methodologically suspect:

- Surely it is a very

arbitrary methodological restriction [assumed in Darwinism] that the organism

must always be conceived of as cut off from its environment, that the interdependence

of object and environment is of only secondary importance, and that the

object's evolution must be treated primarily as a closed causal system!

I would go further . . . and say that such a restriction is not only arbitrary, but also crudely anthropomorphic! For it is just of the human being himself, and only of the human being--and then only since the seventeenth century--that the cutting off from environment is in fact characteristic. (WA 159)

- It offers no explanation of the "problem of unity":

- The Darwinians have,

with their historical investigations, made "species" look silly and unreal

enough--but they have not presented science with any way of getting at

the unity which underlies these innumerable variations--other than the

trivial subterfuge of imagining a very remote time when they did not exist.

(RCA 35)

- It is grounded on circular reasoning:

- The central fortress

[of Darwinism], then, is the "primeval" inorganic solidity of the earth.

. . . On the one hand it is said that the earth as we know it, including

its "secondary" quality of solidity, is a construct of the human brain;

and, thus, that brain and solidity are correlatives; on the other hand,

it is assumed that the earth as we know it was there for billions of years

before there was a human, or any other brain, in existence. (WA

157)

- And--its greatest fault--Darwinism essentially leaves out of the picture the central enigma (the "original mystery," as mathematician G. Spencer-Brown terms it) of how human consciousness--the source, self-reflexively, of the idea of evolution in the first place--came to be: the huge question--answered by Anthroposophy's conception of the evolution of consciousness--of how material evolution ever gave rise to mind.

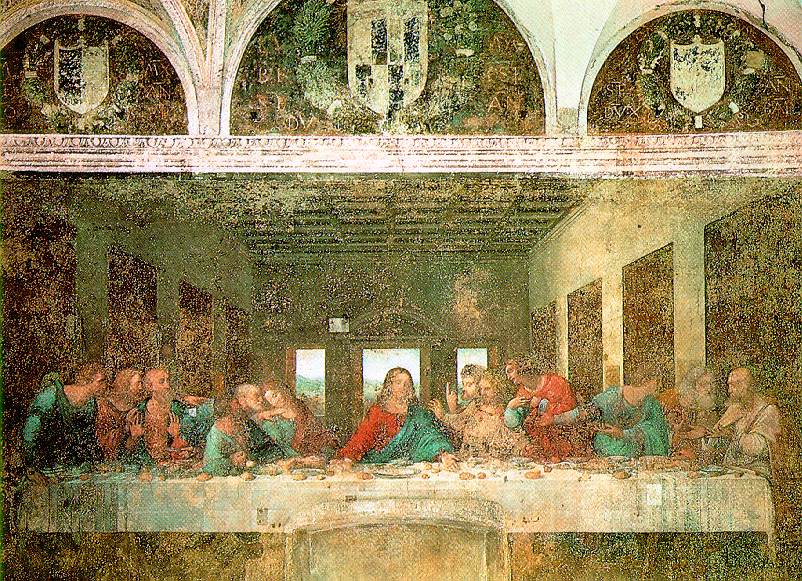

- Burgeon decided

that he at any rate must leave nature alone and confine himself to spotting

the working of the two adversaries in the mind of man. As to evolution--Good

Heavens! He suddenly saw in a blinding light what they had done--not indeed

with biological evolution itself, but with the picture men had formed of

that evolution. The picture they had induced us to form was one of a cosmic

process in which nothing but Lucifer and

Ahriman

were at work; of a process which they and they alone could have brought

about! It was a process of transformation, from which transformation itself

had been eliminated! Men spoke of evolution and described--a succession

of substitutions. . . . This, then, was the picture we were left with--the

two opposing influences so clearly seen, the two sides of the canvas so

delicately painted--and the central figure, which alone gave meaning to

them, omitted! It was like--it was like--and he found himself striving

to imagine what manner of picture Leonardo

da Vinci's Last

Supper would be with the central figure blacked out. (UV

67-68)3

A touch of that participation which still linked the Greeks, and even the medieval observer with his phenomena, might well have led to a very different interpretation--as it did in the case of Goethe, who had that touch. But for the generality of men, participation was dead; the only link with the phenomena was through the senses; and they could no longer conceive of any manner in which either growth itself or the metamorphoses of individual and special growth, could be determined from within. The appearances were idols. They had no "within." Therefore the evolution which had produced them could only be conceived mechanomorphically as a series of impacts of idols on other idols. (SA 61-63)

| See in particular "The Evolution Complex" and Saving the Appearances, Chaps. VII, VIII, IX, X. |

| 1Darwinism, Barfield goes on to note, "seized hold of the imagination, at first of the English-speaking, and then of the whole Western world, with a rapidity and an all-exclusiveness which I believe future generations will contemplate as a startling historical phenomenon. . . . It has almost become subconscious" (EC 8). |

| 2"The light of reason," Barfield observes caustically, "was not Charles Darwin's guiding star. Which makes it all the stranger that his own thinking should have remained the guiding star for western science and western thinking in general for something like one-and-a-half centuries" (EC 12). |

3The

Meggid provides Burgeon with an even deeper understanding of the Anthroposophical

perspective on the success of Darwinism:

|

| 4"I have no doubt [Barfield has Sanderson say in Worlds Apart] that [natural selection] was an important physical factor; I only think its significance has been exaggerated. I don't mean the theory that the human form has evolved from the animal form. Physically speaking, I think it largely did. I mean the assumption that organic matter evolved from inorganic, and that the phenomenon of solidity preceded the phenomenon of life. In my view these are both not only pure assumptions but also largely arbitrary one" (WA 156, Sanderson is speaking). |