Bacon

Copernicus

Galileo

| Chronological Snobbery |

The young physicist Ranger in Worlds Apart epitomizes chronological snobbery. See, for example, the following pontification:

"You see, I have the advantage of knowing something of what is actually going on. I don't know much about the history of science and still less about the history of pre-scientific thought. What I do know is, that three or four hundred years ago for some reason or other the human mind suddenly woke up. I don't know who started it--Bacon, Copernicus, Galileo, or someone--and it doesn't seem to me to matter. The point is, that for some reason people began to look at the world around them instead of accepting traditional theories, to explore the universe instead of just sitting around and thinking about it. First of all they discovered that the earth wasn't flat . . . and that it was not the centre of the universe, as they had been dreaming, but a rapidly revolving and whirling speck of dust in empty space. Almost overnight about half the ideas men had had about the universe and their own place in it, turned out to be mere illusions. And the other half went the same way, when scientists began applying the new method--practical exploration--to other fields of inquiry--mechanics, chemistry, physiology, biology, and, later on, animal and human psychology and so forth. Everything that had been thought before, from the beginnings of civilization down to that moment, became hopelessly out of date and discredited. I suppose it still has an interest for antiquarians and historical specialists and similar types, but apart from that. . . ." [WA 13-14)

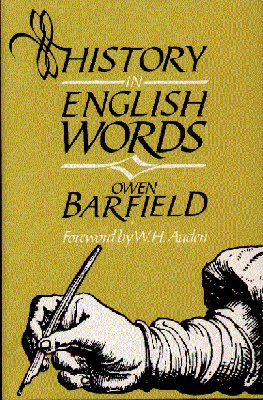

| See in particular History, Guilt and Habit, passim and History in English Words, passim. |

| 1"But this sense of the past as 'something different' is almost inseparable from another element in our own concern with history, namely, the habit of looking on the past as a sort of seed, of which the present is the transformation or fruit. This 'developmental' view of the nature of time past seems to us so obvious as to make it almost nonsensical to put it into words; for whether we think of history in general as a meaningful process or as a meaningless one, we just cannot help thinking of it as the old gradually giving way to the new. Yet that whole way of thinking is hardly more than two or three centuries old. It began only when another important change had just been taking place in the West in man's ideas about the relation between the past and present . . .: the abandonment of the medieval and classical conviction that the history of mankind as a whole was a process of degeneration, and the substitution therefore of the conviction that the history of man is one of progress. Hitherto it had been thought of as a descent from a Golden Age in the past; now it began to be thought of as an ascent into a golden age in the future" (SM 15-16). |

2G. B. Tennyson

offers the following first-hand account of chronological snobbery in action:

|