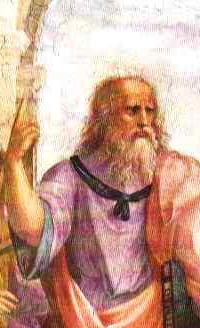

Plato

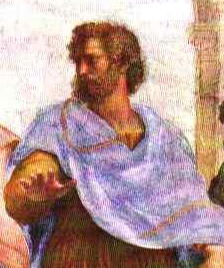

Aristotle

Dante

| Nominalism |

In Poetic Diction,

Barfield observes, while tracing the history of what he calls "the prosaic

principle," how an historian of language "might note . . . that the increased

action of this principle was accompanied by the birth of hitherto unknown

antitheses, such as those between truth and myth, between prose and poetry,

and again between an objective and a subjective world; so that now, for

the first time, it becomes possible to distinguish the content of a word

from its reference." He might, moreover,

look to the history of philosophy for some indication of the moment at which the ascending rational principle and the descending poetic principle (for, in certain respects, we can think of them as of two buckets in a well) are passing one another. If so, I think he would fix on the prominence in men's minds of the metaphysical problem of "universals." For when the number of general ideas arrived at by abstractions . . . is rapidly increasing, and yet there is still a strong sense of the old, concrete, unitary meanings, it is natural that the coexistence of two kinds of universal should arouse confusion. Are universals real beings, it is asked, or mere classifying abstractions in the minds of men, evolved for the convenience of quick thinking. The latter (Nominalist-Conceptualist) verdict, if applied indiscriminately to all universals, may be compared with the error . . . by which an adult thinker reads his own generalizations into a child's mind. (94-95)Thus nominalism represents but the latest, penultimate phase in a centuries long process:

The old, instinctive consciousness of single meanings, which comes down to us as the Greek myths, is already fighting for its life by Plato's time as the doctrine of Platonic Ideas (not "abstract," though this word is often erroneously used in English translations); Aristotle's logic and his Categories, as interpreted by his followers, then tend to concentrate attention exclusively on the abstract universals, and so to destroy the balance; and then again the form and entelechies of Aristotle are brought to life in the poetry of Dante as the Heavenly Hierarchies; and yet again, Nominalism, with its legacy of modern empirical philosophy and science, obscures men's minds of all but the abstract universals. (PD 95)1

| See in particular "Language and Poetry" (PD 93-101), "Devotion" (HEW 118-38). |

| 1As Barfield shows in History in English Words, the invention of the nominalist position was not limited to the Judeo-Christian philosophical tradition, for "The Arab seems to have possessed something of that combination of materialism on the one hand and excessive intellectual abstraction on the other which we [notice] in the later stages of Roman mythology. Just as he made Mohammedanism out of the Jewish sacred traditions, he made Nominalism out of Greek philosophy. The influence upon Christian thought of great Arabic philosophers like Averroes and Avicenna is one of the most astonishing chapters in its history" (HEW 132-33). |