Monod

G. Steiner

| Evolution of Consciousness |

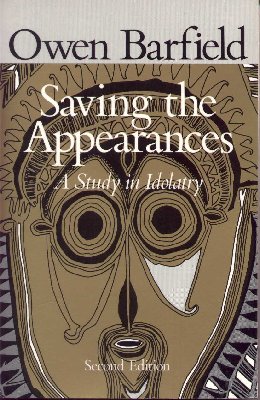

I think the same; but I do not see that responsibility at all as others see it. George Steiner once coined a useful phrase when he referred to our contemporary habit of "biologizing the data," and these people all seem to think only in terms of an evolution biologically determined, and therefore of the application of technology to the data, whether by genetic engineering or otherwise. Whereas I am certain that our responsibility will only be discharged, if at all, not by tinkering with the outside of the world but by changing it, slowly no doubt, from the inside. (92)Such change can never come about, however, without full realization of what Barfield deems the evolution of consciousness.

"The actual evolution of the earth we know," Barfield insists, "must have been at the same time an evolution of consciousness" (SA 65). Evolution has not been the "haphazard affair" (UV 50) it is now supposed to be. It has not been the result only of chance and necessity (as Jacques Monod has argued), but is, Barfield has shown, guided by a telos which modern science refuses to recognize. This telos is the evolution of consciousness, and at its center lies the emergence of the human mind and the evolution of anthropocentricity.

Our understanding

of evolution, Darwinism, has from the start

been a victim of our idolatry and thus presents us only with half-truths:

With the doctrine of evolution the concept of "man," as a thinkable entity, with a history behind him and a destiny in front of him, made a first confused reappearance. But owing to the form which that doctrine took under the influence of the prevailing idolatry, this "man" of evolution has no inner unity with the spirit of any particular man alive on earth at any particular moment. When the evolution of phenomena is substituted for our supposed evolution of idols, it will, I believe, be seen without much difficulty that the evolution of the individual human spirit has always proceeded step by step with the evolution of nature; and that both are indeed "fallen." The biological evolution of the human race is, in fact, only one half of the story; the other has still to be told. (SA 184)The discovery of evolution in the 18th and 19th centuries offered the human mind a radical new way of looking at life on Earth and our place within it, but that realization will , Barfield is convinced, pale by comparison to the new understanding likely to follow in the wake of the acceptance of the evolution of consciousness:

- If the eighteenth-century

botanist, looking for the first time through the old idols of Linnaeus's

fixed and timeless classification into the new perspective of biological

evolution felt a sense of liberation and of light, it can have been but

a candle-flame compared with the first glimpse we now get of the familiar

world and human history lying together, bathed in the light of the evolution

of consciousness. (SA 72)

| Consciousness Soul | Astral Body |

| Intellectual Soul | Etheric Body |

| Sentient Soul | Physical Body |

| Remoter Future | Spirit Man |

| Seventh Civilization | Life Spirit |

| Sixth Civilization | Spirit Self |

| A. D. 1450--now | Consciousness Soul |

| B.C. 750--A.D. 1450 (Graeco-Roman Period | Intellectual Soul |

| Egypto-Chaldean Period | Sentient Body |

| Ancient Persian Period | Astral Body |

| Ancient Indian Period | Etheric Body |

| Remoter Past | Physical Body |

(RCA 98)

Barfield offers numerous striking prose analogies for his understanding of the evolution of consciousness. Here are two of the most illuminating:

- We may very well compare the self of man to a seed. Formerly what is now the seed was a member of the old plant, and as such was wholly informed with a life not wholly its own. But now the pod or capsule has split open, and the dry seed has been ejected. It has attained to a separate existence. Henceforth one of two things may happen to it: either it may abide alone, isolated from the rest of the earth, growing dryer and dryer, until it withers up altogether; or, by uniting with the earth it may blossom into a fresh life of its own. . . . uniting itself with the Spirit of the Earth, with the Word, it may blossom into the imaginative soul, and live. It differs from the seed only in this, that the choice lies with itself. (RCA 79-80)

- If you want to represent the process of evolution diagrammatically, you must think, not as the evolutionary humanists do, of a straight line sloping on and on and on and up and up and up, but rather of a curve like a capital "U" Now, if you move down the left-hand side, or limb of a letter "U," round the curve at the bottom and up the right-hand limb, you will keep on reaching points on the right side which are at the same level as corresponding points on the left; and these levels you certainly did pass on your way down. The journey on will, by its nature--to that extent--involve a journey back, or a return. . . . Oddly enough, it is very much the same with a clock. It is not only when you move the hands backwards that you bring them back to where they were before; you also do it when you move them forwards. (RCA 230-31)

| See in particular Romanticism Comes of Age, passim. |