We are haunted by Martin Heidegger. Even if you’ve never read a word of his dense philosophical texts, his ghost walks beside you, shaping how you imagine your place in the world. His spectral influence permeates our modern consciousness, guiding how we understand our relationship to reality, technology, and meaning itself. Heidegger’s philosophical project emerged as a desperate attempt to resolve the existential crisis that had been brewing in Western thought explicitly since the Romantic era—a crisis most eloquently articulated by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who recognised the growing chasm between subjective experience and the objective world.

Coleridge had warned that the Enlightenment’s mechanical view of nature was creating a dangerous split in human consciousness. We were becoming, in his words, “souls in a state of morbid estrangement,” increasingly unable to find our authentic place in a world reduced to mathematical equations and mechanical principles. This rupture demanded resolution, and Heidegger’s response was as influential as it was problematic: he attempted to ground all meaning and imagination within the subjective experience of the self, the individual Dasein (“being-there”) thrown into existence. In Heidegger’s framework, authenticity emerges not from harmonious integration with the world but from confronting one’s own mortality and making resolute choices within an essentially meaningless cosmos. The world becomes primarily the stage upon which the drama of human self-creation unfolds. This philosophical move, while offering temporary shelter from nihilism, ultimately deepened our sense of alienation by cementing the primacy of subjective experience over any external order or meaning.

Martin Heidegger, in 1960. (Photo by Willy Pragher, reproduced under a Creative Common license 3.0.)

The consequences of this Heideggerian turn are everywhere in our twenty-first century struggles. Our culture’s obsession with self-determination, authentic self-expression, and personal identity— divorced from any larger sense of cosmic order or natural harmony—flows directly from this philosophical watershed. We find ourselves increasingly isolated in bubbles of subjective experience, unable to forge meaningful connections between our interior lives and the objective world we inhabit. Technology, once hoped to be our salvation, has only intensified this isolation, creating digital realms where self-expression flourishes while genuine connection withers. But what if Western thought had taken a different path? What if, instead of following Heidegger’s solution of radical subjectivity, we had been more attentive to his lesser-known contemporary, Owen Barfield? What alternative vision might have shaped our cultural imagination?

Barfield, best known as a member of the Oxford Inklings alongside C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams and J.R.R. Tolkien, offered a fundamentally different response to the same existential crisis. Like Heidegger, Barfield fully recognised the emergence of the wilful, self-conscious subject as the defining feature of modern consciousness. But unlike Heidegger, Barfield didn’t see this as necessitating alienation from the external world. Instead, he proposed a path of integration and participation.

Part of why Barfield’s vision never gained the traction of Heidegger’s may lie in the different philosophical traditions they inhabited. Barfield’s language of “evolution of consciousness” emerged from his unique synthesis of German Idealism, anthroposophy, and English Romanticism—a combination that spoke powerfully to certain audiences while remaining outside mainstream philosophical discourse. His terms “original participation” and “final participation” reflect his ambitious attempt to chart the entire trajectory of human consciousness, whereas Heidegger’s more immediate language of authenticity and resoluteness addressed the existential concerns of his particular moment. Each thinker’s vocabulary served their distinct philosophical projects, though Barfield’s developmental framework would find its greatest reception among those already sympathetic to evolutionary and spiritual perspectives.

What makes Barfield’s contribution particularly valuable is how his distinctive terminology opens up dimensions of experience that other philosophical vocabularies might miss. In works like Saving the Appearances and Poetic Diction, he articulated a view of consciousness as dynamic rather than static. For him, human consciousness had moved from a pre-modern state where humans experienced themselves as embedded within nature, unable to distinguish clearly between inner and outer reality, to our current state of alienated self-consciousness, where we experience ourselves as isolated observers of an external, mechanistic world. His specific language choices—however unfamiliar they might initially seem—capture nuances of this transformation that more conventional philosophical terms might obscure.

Crucially, Barfield didn’t believe this alienation was our final destination. He envisioned a third stage where we might recover a sense of meaningful connection with the world not through regression to pre-modern consciousness but through a deliberate, conscious act of imaginative participation. The imagination, for Barfield, wasn’t merely subjective fantasy but the faculty through which we could genuinely perceive the meaningful patterns and relationships that constitute reality itself.

We must imagine in order to know, Barfield insisted, turning on its head the conventional wisdom that imagination distorts objective reality. For him, imagination properly disciplined was not opposed to truth but essential to perceiving it. This position stands in stark contrast to Heidegger’s emphasis on resoluteness in the face of meaninglessness, offering instead the possibility of discovering genuine meaning through active, conscious participation in reality. What might our world look like had Barfield’s vision, rather than Heidegger’s, shaped our cultural imagination? The differences would be profound and startlingly relevant to our contemporary crises.

Our relationship with technology might be fundamentally reframed. Where Heidegger’s thought ultimately positions technology as an expression of human will-to-power—something we can critique but never truly integrate—Barfield offers the possibility of technology as medium for renewed participation. Digital spaces need not be escapist bubbles of subjective experience but could function as new domains for meaningful engagement with patterns of reality. The current bifurcation between digital natives lost in virtual worlds and neo-Luddites rejecting technology altogether might give way to more integrative approaches where technology serves as bridge rather than barrier between self and world.

Our ecological crisis might be approached with different conceptual tools. The current environmental discourse often oscillates between utilitarian resource management and romantic nature worship—both inadequate frameworks. Barfield’s understanding of participatory imagination suggests a third possibility: recognising that nature is neither mere resource nor sacred other, but a reality with which human consciousness has co-evolved and in which we might consciously participate. This shifts environmental ethics from either exploitation or hands-off preservation toward active, imaginative stewardship.

Perhaps most significantly, our fragmented cultural landscape might find paths toward greater coherence. The polarisation between traditionalists who insist on objective meaning and progressives who champion subjective construction reflects precisely the false dichotomy Barfield sought to transcend. His vision suggests that meaning emerges neither from mere discovery nor from mere invention but through the participatory dance between human consciousness and the world it inhabits. This middle path might offer desperately needed common ground in our fractured discourse.

What’s particularly intriguing is how Barfield’s thinking anticipates contemporary developments across multiple disciplines. Recent work in cognitive science increasingly recognises that perception is neither passive reception nor pure construction but an active, participatory process. Quantum physics continues to blur the line between observer and observed in ways that resonate with Barfield’s participatory framework. Even in digital culture, there’s growing recognition that pure virtuality proves ultimately unsatisfying—that meaningful experience requires embodied engagement with material reality.

Had we listened more carefully to Barfield, we might have avoided some of the oscillations that have characterised post-Heideggerian thought. Rather than swinging between existential authenticity and postmodern deconstruction, between the heroic subject creating meaning and the dissolved subject awash in language games, we might have developed a more balanced understanding of human consciousness as both genuinely creative and genuinely responsive to patterns beyond itself.

It’s not too late for Barfield’s vision to find new resonance. Stripped of its dated evolutionary language and reframed in terms more accessible to contemporary thought—participatory imagination, conscious reintegration, attentive presence—his fundamental insights offer precisely what we now struggle to articulate: a way of being that is neither domineering nor passive, neither solipsistically self-creating nor blindly conformist.

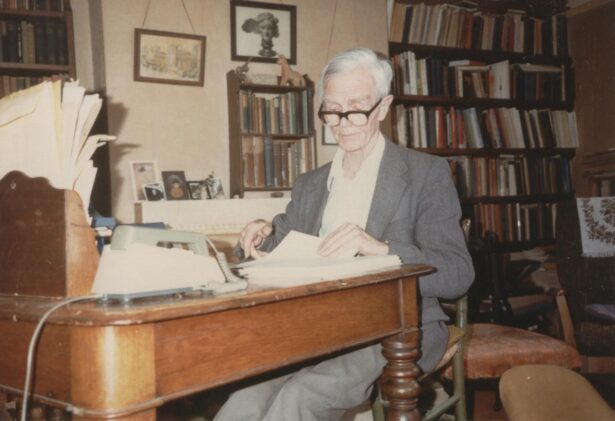

Owen Barfield in his study in the early 1980s

Like Coleridge before him, the imagination Barfield champions isn’t mere fantasy or subjective projection but a faculty of genuine perception, one that allows us to apprehend meaningful patterns that exist independent of us yet require our participation to be fully realised. In a world increasingly divided between those who insist on objective facts and those who champion subjective truths, this middle path of participatory imagination offers a way forward that honours both the independence of reality and the creative role of human consciousness.

We remain haunted by Heidegger, but perhaps we can begin to recognise Barfield’s quieter ghost as well, offering an alternative vision of what it means to be human in a meaningful world. The existential anxiety Heidegger diagnosed need not lead to heroic self-assertion in a meaningless cosmos but might instead open us to more attentive, imaginative participation in a reality that both transcends us and invites our creative engagement. In choosing between these philosophical paths, we may be deciding nothing less than how we will inhabit the planet—whether as isolated subjects imposing our will upon passive matter or as conscious participants in a meaningful dance that preceded us and will continue long after we’re gone.

*

Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1976) was a German philosopher who was particularly interested in questions of ontology and phenomenology. He has had a substantial influence in subsequent western philosophy. His most famous work is Being and Time, and other prominent works include the Letter on Humanism and What is Called Thinking?